Evaṁ me sutaṁ—ekaṁ samayaṁ bhagavā sāvatthiyaṁ viharati jetavane anāthapiṇḍikassa ārāme.

Thus have I heard—At one time, the Blessed One was dwelling at Sāvatthi, in Jeta’s grove, Anāthapiṇḍika’s park.

Atha kho sambahulānaṁ bhikkhūnaṁ pacchābhattaṁ piṇḍapātapaṭikkantānaṁ upaṭṭhānasālāyaṁ sannisinnānaṁ sannipatitānaṁ ayamantarākathā udapādi:

Then, after their meal, when many bhikkhus had returned from their alms round and were seated together in the assembly hall, this |this conversation::this discussion, lit. this in-between talk [ayamantarākathā]| arose among them:

“acchariyaṁ, āvuso, abbhutaṁ, āvuso. Yāvañcidaṁ tena bhagavatā jānatā passatā arahatā sammāsambuddhena kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā mahapphalā vuttā mahānisaṁsā”ti.

“It is wonderful, friends, it is marvelous, how the Blessed One who knows and sees, the |Arahant::a worthy one, a fully awakened being, epithet of the Buddha [arahant]|, the perfectly Awakened One, has said that mindfulness of the body, when cultivated and frequently practiced, is of great fruit and great benefit.”

Ayañca hidaṁ tesaṁ bhikkhūnaṁ antarākathā vippakatā hoti, atha kho bhagavā sāyanhasamayaṁ paṭisallānā vuṭṭhito yena upaṭṭhānasālā tenupasaṅkami; upasaṅkamitvā paññatte āsane nisīdi. Nisajja kho bhagavā bhikkhū āmantesi: “kāya nuttha, bhikkhave, etarahi kathāya sannisinnā, kā ca pana vo antarākathā vippakatā”ti?

And this discussion among the bhikkhus was left unfinished. For the Blessed One, having emerged from |seclusion::solitude, privacy [paṭisallāna]| in the late afternoon, approached the assembly hall, and sat down on the prepared seat. Once he was seated, the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus: “Bhikkhus, for what topic of conversation are you now seated together here? And what was the discussion among you that was left unfinished?”

“Idha, bhante, amhākaṁ pacchābhattaṁ piṇḍapātapaṭikkantānaṁ upaṭṭhānasālāyaṁ sannisinnānaṁ sannipatitānaṁ ayamantarākathā udapādi: ‘acchariyaṁ, āvuso, abbhutaṁ, āvuso. Yāvañcidaṁ tena bhagavatā jānatā passatā arahatā sammāsambuddhena kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā mahapphalā vuttā mahānisaṁsā’ti. Ayaṁ kho no, bhante, antarākathā vippakatā, atha bhagavā anuppatto”ti.

“Here, venerable sir, after we had returned from our alms round following the meal, we were seated together in the assembly hall when this conversation arose among us: ‘It is wonderful, friends, it is marvelous, how the Blessed One who knows and sees, the Arahant, the perfectly Awakened One, has said that mindfulness of the body, when cultivated and frequently practiced, is of great fruit and great benefit.’ And this was the discussion, venerable sir, that was left unfinished when the Blessed One arrived.”

“Kathaṁ bhāvitā ca, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati kathaṁ bahulīkatā mahapphalā hoti mahānisaṁsā?

“And how, bhikkhus, is mindfulness of the body cultivated and frequently practiced so that it is of great fruit and great benefit?

Body Contemplation with Breathing

Idha, bhikkhave, bhikkhu araññagato vā rukkhamūlagato vā suññāgāragato vā nisīdati pallaṅkaṁ ābhujitvā ujuṁ kāyaṁ paṇidhāya parimukhaṁ satiṁ upaṭṭhapetvā. So satova assasati satova passasati; dīghaṁ vā assasanto ‘dīghaṁ assasāmī’ti pajānāti, dīghaṁ vā passasanto ‘dīghaṁ passasāmī’ti pajānāti; rassaṁ vā assasanto ‘rassaṁ assasāmī’ti pajānāti, rassaṁ vā passasanto ‘rassaṁ passasāmī’ti pajānāti; ‘sabbakāyapaṭisaṁvedī assasissāmī’ti sikkhati, ‘sabbakāyapaṭisaṁvedī passasissāmī’ti sikkhati; ‘passambhayaṁ kāyasaṅkhāraṁ assasissāmī’ti sikkhati, ‘passambhayaṁ kāyasaṅkhāraṁ passasissāmī’ti sikkhati. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

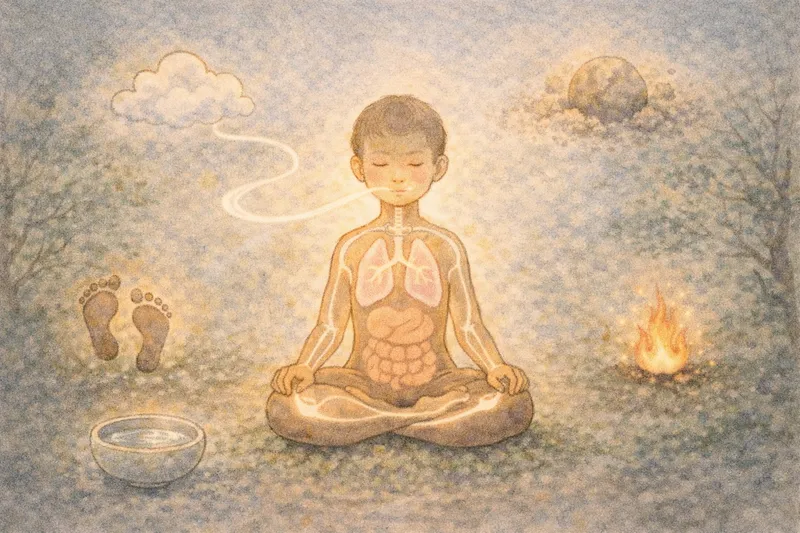

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, having gone to the forest, to the foot of a tree, or to an empty dwelling, sits down, folding his legs crosswise, setting his body upright, establishing mindfulness as first priority. Ever mindful, he breathes in; ever mindful, he breathes out. Breathing in long, he |discerns::distinguishes, understands, knows clearly [pajānāti]|, ‘I am breathing in long;’ breathing out long, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out long.’ Breathing in short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing in short;’ breathing out short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out short.’ He trains thus, ‘While breathing in, I shall |experience the whole body::be conscious of the whole body, be sensitive to the whole process [sabbakāyapaṭisaṃvedī]|;’ he trains thus, ‘While breathing out, I shall experience the whole body.’ He trains thus, ‘While breathing in, I shall |settle::calm, still [passambhayanta]| the |bodily constructs::bodily processes associated with breathing, specifically the in-and-out breath. It encompasses the physical movements and sensations that arise from the act of breathing. [kāyasaṅkhāra]|;’ he trains thus, ‘While breathing out, I shall settle the bodily constructs.’ As he dwells thus—|diligent::doing one’s work or duty well, with alertness, carefulness and care [appamatta]|, |resolute::determined, intent [pahitatta]|, and |with continuous effort::ardent, zealous, with energy, with application [ātāpī]|—his worldly |memories and thoughts::memories and plans [sarasaṅkappā]| are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and |collected::composed, stable [samādhiyati]|. In this way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Body Contemplation in Postures

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu gacchanto vā ‘gacchāmī’ti pajānāti, ṭhito vā ‘ṭhitomhī’ti pajānāti, nisinno vā ‘nisinnomhī’ti pajānāti, sayāno vā ‘sayānomhī’ti pajānāti. Yathā yathā vā panassa kāyo paṇihito hoti tathā tathā naṁ pajānāti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, when walking, a bhikkhu discerns, ‘I am walking;’ when standing, he discerns, ‘I am standing;’ when sitting, he discerns, ‘I am seated;’ when lying down, he discerns, ‘I am lying down.’ In whatever way his body is |oriented::disposed; lit. placed down forward [paṇihita]|, he discerns it accordingly. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Body Contemplation with Clear Awareness

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu abhikkante paṭikkante sampajānakārī hoti, ālokite vilokite sampajānakārī hoti, samiñjite pasārite sampajānakārī hoti, saṅghāṭipattacīvaradhāraṇe sampajānakārī hoti, asite pīte khāyite sāyite sampajānakārī hoti, uccārapassāvakamme sampajānakārī hoti, gate ṭhite nisinne sutte jāgarite bhāsite tuṇhībhāve sampajānakārī hoti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu acts with |clear awareness::attentiveness, clear and full comprehension [sampajañña]| when going forward and returning; he acts with clear awareness when looking ahead and looking around; he acts with clear awareness when bending back and stretching out; he acts with clear awareness when wearing robes and carrying outer robe and bowl; he acts with clear awareness when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting; he acts with clear awareness when defecating and urinating; he acts with clear awareness when walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, waking up, speaking, and keeping silent. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Contemplating the Disagreeable in the Body

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ uddhaṁ pādatalā adho kesamatthakā tacapariyantaṁ pūraṁ nānappakārassa asucino paccavekkhati: ‘atthi imasmiṁ kāye kesā lomā nakhā dantā taco maṁsaṁ nhāru aṭṭhi aṭṭhimiñjaṁ vakkaṁ hadayaṁ yakanaṁ kilomakaṁ pihakaṁ papphāsaṁ antaṁ antaguṇaṁ udariyaṁ karīsaṁ pittaṁ semhaṁ pubbo lohitaṁ sedo medo assu vasā kheḷo siṅghāṇikā lasikā muttan’ti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu |reviews::considers, reflects, regards [paccavekkhati]| this very body from the soles of the feet upwards and from the top of the hair downwards, bounded by skin and full of various impurities thus: ‘In this body, there are hairs of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin; flesh, |sinews::tendons and ligaments connecting muscle to bone [nhāru]|, bones, |bone marrow::the soft tissue inside the bones [aṭṭhimiñjaṁ]|, kidneys; heart, liver, |inner membrane::the pleura or fascia wrapping the organs [kilomaka]|, |spleen::the blood-filtering organ under the left ribs [pihaka]|, lungs; intestines, |mesentery::the tissue binding the intestines; lit. intestine string [antaguṇa]|, |stomach contents::undigested food; lit. related to the belly [udariya]|, |feces::excrement, digested waste [karīsaṁ]|, [brain]; |bile::digestive fluid, usually visualized in the gall bladder [pittaṁ]|, |phlegm::mucus of the respiratory tract [semha]|, |pus::fluid resulting from infection or decay [pubba]|, blood, |sweat::perspiration exuded from pore spaces [seda]|, |fat::thick, adipose tissue [meda]|, tears, |grease::liquid fat or skin oils (distinct from solid fat) [vasā]|, saliva, |nasal mucus::snot, fluid from the nose [siṅghāṇikā]|, |synovial fluid::lubricating fluid inside the joints [lasikā]|, and |urine::liquid waste stored in the bladder [mutta]|.’

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, ubhatomukhā putoḷi pūrā nānāvihitassa dhaññassa, seyyathidaṁ—sālīnaṁ vīhīnaṁ muggānaṁ māsānaṁ tilānaṁ taṇḍulānaṁ, tamenaṁ cakkhumā puriso muñcitvā paccavekkheyya: ‘ime sālī ime vīhī ime muggā ime māsā ime tilā ime taṇḍulā’ti; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ uddhaṁ pādatalā adho kesamatthakā tacapariyantaṁ pūraṁ nānappakārassa asucino paccavekkhati: ‘atthi imasmiṁ kāye kesā lomā nakhā dantā taco maṁsaṁ nhāru aṭṭhi aṭṭhimiñjaṁ vakkaṁ hadayaṁ yakanaṁ kilomakaṁ pihakaṁ papphāsaṁ antaṁ antaguṇaṁ udariyaṁ karīsaṁ pittaṁ semhaṁ pubbo lohitaṁ sedo medo assu vasā kheḷo siṅghāṇikā lasikā muttan’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Just as if, bhikkhus, there were a bag with an opening at both ends full of many sorts of grains, such as rice, barley, beans, peas, millet, and white rice, and a man with good eyesight having opened it were to reflect, ‘These are rice, these are barley, these are beans, these are peas, these are millet, these are white rice.’ In just the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body from the soles of the feet upwards and from the top of the hair downwards, bounded by skin and full of various impurities thus: ‘In this body, there are hairs of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin; flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys; heart, liver, inner membrane, spleen, lungs; intestines, mesentery, stomach contents, feces, [brain]; bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid, and urine.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Contemplating the Elements in the Body

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ yathāṭhitaṁ yathāpaṇihitaṁ dhātuso paccavekkhati: ‘atthi imasmiṁ kāye pathavīdhātu āpodhātu tejodhātu vāyodhātū’ti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body, in whatever way it is positioned, in whatever way it is oriented, considering it in terms of the elements thus: ‘In this body, there is the |earth element::whatever internal or external that is solid, hard, resistant, appears stable and supporting, which can be considered as belonging to oneself, and can be clung to [pathavīdhātu]|, the |water element::whatever internal or external, that is liquid, cohesive, flowing, binding, moist, which can be considered as belonging to oneself, and can be clung to [āpodhātu]|, the |fire element::whatever internal or external that is hot, fiery, transformative, warming, cooling, which can be considered as belonging to oneself and can be clung to [tejodhātu]|, and the |wind element::whatever internal or external that is airy, gaseous, moving, vibrating, wind-like, which can be considered as belonging to oneself and can be clung to [vāyodhātu]|.’

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, dakkho goghātako vā goghātakantevāsī vā gāviṁ vadhitvā catumahāpathe bilaso vibhajitvā nisinno assa; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ yathāṭhitaṁ yathāpaṇihitaṁ dhātuso paccavekkhati: ‘atthi imasmiṁ kāye pathavīdhātu āpodhātu tejodhātu vāyodhātū’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Just as if, bhikkhus, a skilled butcher or their apprentice, having slaughtered a cow, were sitting at a crossroads, having divided it up piece by piece; in just the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body, however it is positioned, in whatever way it is oriented, considering it in terms of the elements thus: ‘In this body, there is the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the wind element.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

The Nine Charnel Ground Contemplations

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu seyyathāpi passeyya sarīraṁ sivathikāya chaḍḍitaṁ ekāhamataṁ vā dvīhamataṁ vā tīhamataṁ vā uddhumātakaṁ vinīlakaṁ vipubbakajātaṁ. So imameva kāyaṁ upasaṁharati: ‘ayampi kho kāyo evaṁdhammo evaṁbhāvī evaṁanatīto’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a |charnel ground::an above-ground site for the putrefaction of bodies, generally human, where formerly living tissue is left to decompose uncovered [sivathikā]| one day dead, two days dead, or three days dead, bloated, discolored, and decomposing, a bhikkhu |compares::likens; lit. brings near together [upasaṁharati]| this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu seyyathāpi passeyya sarīraṁ sivathikāya chaḍḍitaṁ kākehi vā khajjamānaṁ kulalehi vā khajjamānaṁ gijjhehi vā khajjamānaṁ kaṅkehi vā khajjamānaṁ sunakhehi vā khajjamānaṁ byagghehi vā khajjamānaṁ dīpīhi vā khajjamānaṁ siṅgālehi vā khajjamānaṁ vividhehi vā pāṇakajātehi khajjamānaṁ. So imameva kāyaṁ upasaṁharati: ‘ayampi kho kāyo evaṁdhammo evaṁbhāvī evaṁanatīto’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa …pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, being eaten by crows, or hawks, or vultures, or herons, or dogs, or tigers, or leopards, or jackals, or by various kinds of creatures, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu seyyathāpi passeyya sarīraṁ sivathikāya chaḍḍitaṁ aṭṭhikasaṅkhalikaṁ samaṁsalohitaṁ nhārusambandhaṁ …pe… aṭṭhikasaṅkhalikaṁ nimmaṁsalohitamakkhitaṁ nhārusambandhaṁ …pe… aṭṭhikasaṅkhalikaṁ apagatamaṁsalohitaṁ nhārusambandhaṁ …pe… aṭṭhikāni apagatasambandhāni disāvidisāvikkhittāni aññena hatthaṭṭhikaṁ aññena pādaṭṭhikaṁ aññena gopphakaṭṭhikaṁ aññena jaṅghaṭṭhikaṁ aññena ūruṭṭhikaṁ aññena kaṭiṭṭhikaṁ aññena phāsukaṭṭhikaṁ aññena piṭṭhiṭṭhikaṁ aññena khandhaṭṭhikaṁ aññena gīvaṭṭhikaṁ aññena hanukaṭṭhikaṁ aññena dantaṭṭhikaṁ aññena sīsakaṭāhaṁ. So imameva kāyaṁ upasaṁharati: ‘ayampi kho kāyo evaṁdhammo evaṁbhāvī evaṁanatīto’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa …pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, a skeleton with flesh and blood and held together by sinews; or a skeleton without flesh but smeared with blood and held together by sinews; or a skeleton devoid of flesh and blood and held together by sinews; or bones disconnected and scattered in all directions—here a hand bone, there a foot bone, there an ankle bone, here a shin bone, there a thigh bone, here a pelvis bone, there a rib, here a spine, there a shoulder blade, here a neck bone, there a jawbone, here a tooth, and there a skull, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu seyyathāpi passeyya sarīraṁ sivathikāya chaḍḍitaṁ—aṭṭhikāni setāni saṅkhavaṇṇapaṭibhāgāni …pe… aṭṭhikāni puñjakitāni terovassikāni …pe… aṭṭhikāni pūtīni cuṇṇakajātāni. So imameva kāyaṁ upasaṁharati: ‘ayampi kho kāyo evaṁdhammo evaṁbhāvī evaṁanatīto’ti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa … pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, bones bleached white, the color of conch shells; or bones heaped up, having lain for more than a year; or bones that are rotten and reduced to dust, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Four Jhānas

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu vivicceva kāmehi …pe… paṭhamaṁ jhānaṁ upasampajja viharati. So imameva kāyaṁ vivekajena pītisukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa vivekajena pītisukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, dakkho nhāpako vā nhāpakantevāsī vā kaṁsathāle nhānīyacuṇṇāni ākiritvā udakena paripphosakaṁ paripphosakaṁ sanneyya, sāyaṁ nhānīyapiṇḍi snehānugatā snehaparetā santarabāhirā phuṭā snehena na ca pagghariṇī; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ vivekajena pītisukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati; nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa vivekajena pītisukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa … pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, quite secluded from sensual pleasures and |unwholesome::unhealthy, unskillful, unbeneficial, or karmically unprofitable [akusala]| mental states, enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is |accompanied by reflection::with thinking [savitakka]| and |examination::with investigation, evaluation [savicāra]|, |born of seclusion::secluded from the defilements [vivekaja]|, and imbued with |uplifting joy and pleasure::delight and ease; sometimes experienced as ecstasy, intense exhilaration or rapture [pītisukha]|. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of seclusion, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by the uplifting joy born of seclusion. Just as a skilled bath attendant or his apprentice might knead bathing powder in a bronze bowl, sprinkling water again and again until the lump becomes permeated with moisture, saturated inside and out, yet does not drip. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of seclusion, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by the uplifting joy born of seclusion. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu vitakkavicārānaṁ vūpasamā …pe… dutiyaṁ jhānaṁ upasampajja viharati. So imameva kāyaṁ samādhijena pītisukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati; nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa samādhijena pītisukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, udakarahado gambhīro ubbhidodako. Tassa nevassa puratthimāya disāya udakassa āyamukhaṁ na pacchimāya disāya udakassa āyamukhaṁ na uttarāya disāya udakassa āyamukhaṁ na dakkhiṇāya disāya udakassa āyamukhaṁ; devo ca na kālena kālaṁ sammā dhāraṁ anuppaveccheyya; atha kho tamhāva udakarahadā sītā vāridhārā ubbhijjitvā tameva udakarahadaṁ sītena vārinā abhisandeyya parisandeyya paripūreyya paripphareyya, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato udakarahadassa sītena vārinā apphuṭaṁ assa; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ samādhijena pītisukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa samādhijena pītisukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa …pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the |settling::calming, conciliation, subsiding [vūpasama]| of reflection and examination, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the second jhāna, characterized by internal |tranquility::calming, settling, confidence [sampasādana]| and |unification::singleness, integration [ekodibhāva]| of mind, free from reflection and examination, |born of collectedness::born from a stable mind [samādhija]|, and imbued with |uplifting joy and pleasure::delight and ease; sometimes experienced as ecstasy, intense exhilaration or rapture [pītisukha]|. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of collectedness, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by uplifting joy born of collectedness. Just as a deep lake fed by an underground spring—with no inflow from the east direction, west direction, north direction, or the south direction, and no rainclouds showering water—would have cool streams welling up from within to thoroughly suffuse, pervade, fill, and permeate the entire lake, leaving no part uncovered by cool water. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with the uplifting joy born of collectedness, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by uplifting joy born of collectedness. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu pītiyā ca virāgā …pe… tatiyaṁ jhānaṁ upasampajja viharati. So imameva kāyaṁ nippītikena sukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa nippītikena sukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, uppaliniyaṁ vā paduminiyaṁ vā puṇḍarīkiniyaṁ vā appekaccāni uppalāni vā padumāni vā puṇḍarīkāni vā udake jātāni udake saṁvaḍḍhāni udakānuggatāni antonimuggaposīni, tāni yāva caggā yāva ca mūlā sītena vārinā abhisannāni parisannāni paripūrāni paripphuṭāni, nāssa kiñci sabbāvataṁ uppalānaṁ vā padumānaṁ vā puṇḍarīkānaṁ vā sītena vārinā apphuṭaṁ assa; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ nippītikena sukhena abhisandeti parisandeti paripūreti parippharati, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa nippītikena sukhena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa …pe… evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the |fading of desire for::dispassion toward, detachment from [virāga]| uplifting joy, the bhikkhu dwells |equanimous::mental poised, mentally balanced, non-reactive, disregarding [upekkhaka]|, |mindful and clearly aware::attentive and completely comprehending [sata + sampajāna]|, experiencing |pleasure::comfort, contentedness, happiness, ease [sukha]| with the body. He enters and dwells in the third jhāna, which the Noble Ones describe as, ‘one who dwells equanimous, mindful, and at ease.’ He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with pleasure devoid of delight, so that there is no part of his entire body that is not suffused with pleasure devoid of delight. Just as, bhikkhus, in a pond of blue, red, or white lotuses, some lotuses born in the water grow entirely submerged, and remain nourished from within by cool water that thoroughly suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates them from their tips to their roots, leaving no part untouched by cool water. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with pleasure devoid of delight, so that there is no part of his body that is not suffused with pleasure devoid of delight. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu sukhassa ca pahānā …pe… catutthaṁ jhānaṁ upasampajja viharati. So imameva kāyaṁ parisuddhena cetasā pariyodātena pharitvā nisinno hoti; nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa parisuddhena cetasā pariyodātena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, puriso odātena vatthena sasīsaṁ pārupitvā nisinno assa, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa odātena vatthena apphuṭaṁ assa; evameva kho, bhikkhave, bhikkhu imameva kāyaṁ parisuddhena cetasā pariyodātena pharitvā nisinno hoti, nāssa kiñci sabbāvato kāyassa parisuddhena cetasā pariyodātena apphuṭaṁ hoti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati, sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the abandoning of [bodily] pleasure and |pain::discomfort, unpleasantness. In this context, this is referring to bodily pain or sharp sensations. [dukkha]|, and with the prior settling down of |mental pleasure and displeasure::the duality of positive and negative states of mind; mental happiness and mental pain [somanassadomanassa]|, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the fourth jhāna, which is characterized by purification of |mindfulness::recollection of the body, feelings, mind, and mental qualities, observing them clearly with sustained attention, free from craving and distress [sati]| through |equanimity::mental poise, mental balance, equipoise, non-reactivity, composure [upekkhā]|, experiencing a feeling which is neither-painful-nor-pleasant. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with a purified and clear mind, so that there is no part of his body that is not suffused by this purified and clear mind. Just as, bhikkhus, a person covered from head to toe in a spotless white cloth with no part of his body uncovered. In the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu sits pervading this very body with a pure mind, so purified and clarified, that there is no part of his whole body not pervaded by the pure mind. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Similes

Yassa kassaci, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, antogadhāvāssa kusalā dhammā ye keci vijjābhāgiyā. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci mahāsamuddo cetasā phuṭo, antogadhāvāssa kunnadiyo yā kāci samuddaṅgamā; evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, antogadhāvāssa kusalā dhammā ye keci vijjābhāgiyā.

For whomever, bhikkhus, mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, all beneficial |mental qualities::characteristics, traits, and tendencies of the mind, shaped by repeated actions and sustained attention, guided by particular ways of understanding; they may be wholesome or unwholesome, bright or dark [dhammā]| pertaining to wisdom are included within him. Just as, bhikkhus, for whomever the great ocean is encompassed by his mind, all the small rivers that flow to the ocean are included within that; so too, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, all beneficial mental qualities pertaining to wisdom are included within him.

Yassa kassaci, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati abhāvitā abahulīkatā, labhati tassa māro otāraṁ, labhati tassa māro ārammaṇaṁ. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, puriso garukaṁ silāguḷaṁ allamattikāpuñje pakkhipeyya.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, |Māra::the ruler of the sensual realm, often depicted as a tempter who tries to obstruct beings from the path to liberation [māra]| finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him. Suppose, bhikkhus, a man were to throw a heavy lump of rock upon a mound of wet clay.

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu taṁ garukaṁ silāguḷaṁ allamattikāpuñje labhetha otāran”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that heavy lump of rock find an opening in that mound of wet clay?”

“Evaṁ, bhante”.

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati abhāvitā abahulīkatā, labhati tassa māro otāraṁ, labhati tassa māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, sukkhaṁ kaṭṭhaṁ koḷāpaṁ; atha puriso āgaccheyya uttarāraṇiṁ ādāya: ‘aggiṁ abhinibbattessāmi, tejo pātukarissāmī’ti.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a dry sapless piece of wood, and a man were to come with an upper fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu so puriso amuṁ sukkhaṁ kaṭṭhaṁ koḷāpaṁ uttarāraṇiṁ ādāya abhimanthento aggiṁ abhinibbatteyya, tejo pātukareyyā”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by rubbing the dry sapless piece of wood with an upper fire-stick?”

“Evaṁ, bhante”.

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati abhāvitā abahulīkatā, labhati tassa māro otāraṁ, labhati tassa māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, udakamaṇiko ritto tuccho ādhāre ṭhapito; atha puriso āgaccheyya udakabhāraṁ ādāya.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a hollow empty water jar placed on a stand, and a man were to come carrying a load of water.

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu so puriso labhetha udakassa nikkhepanan”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could that man pour the water into it?”

“Evaṁ, bhante”.

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati abhāvitā abahulīkatā, labhati tassa māro otāraṁ, labhati tassa māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Yassa kassaci, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, na tassa labhati māro otāraṁ, na tassa labhati māro ārammaṇaṁ.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, puriso lahukaṁ suttaguḷaṁ sabbasāramaye aggaḷaphalake pakkhipeyya.

Suppose, bhikkhus, a man were to throw a light ball of string onto a door-panel made entirely of heartwood.

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu so puriso taṁ lahukaṁ suttaguḷaṁ sabbasāramaye aggaḷaphalake labhetha otāran”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that light ball of string find an opening in that door-panel made entirely of heartwood?”

“No hetaṁ, bhante”.

“No, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, na tassa labhati māro otāraṁ, na tassa labhati māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, allaṁ kaṭṭhaṁ sasnehaṁ; atha puriso āgaccheyya uttarāraṇiṁ ādāya: ‘aggiṁ abhinibbattessāmi, tejo pātukarissāmī’ti.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a wet sappy piece of wood, and a man were to come with an upper fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu so puriso amuṁ allaṁ kaṭṭhaṁ sasnehaṁ uttarāraṇiṁ ādāya abhimanthento aggiṁ abhinibbatteyya, tejo pātukareyyā”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by rubbing the wet sappy piece of wood with an upper fire-stick?”

“No hetaṁ, bhante”.

“No, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, na tassa labhati māro otāraṁ, na tassa labhati māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, udakamaṇiko pūro udakassa samatittiko kākapeyyo ādhāre ṭhapito; atha puriso āgaccheyya udakabhāraṁ ādāya.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a water jar placed on a stand, filled right up to the brim such that crows could drink from it, and a man were to come carrying a load of water.

Taṁ kiṁ maññatha, bhikkhave, api nu so puriso labhetha udakassa nikkhepanan”ti?

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could that man pour the water into it?”

“No hetaṁ, bhante”.

“No, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, na tassa labhati māro otāraṁ, na tassa labhati māro ārammaṇaṁ.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Yassa kassaci, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, so yassa yassa abhiññāsacchikaraṇīyassa dhammassa cittaṁ abhininnāmeti abhiññāsacchikiriyāya, tatra tatreva sakkhibhabbataṁ pāpuṇāti sati satiāyatane.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by |direct knowledge::experiential understanding [abhiññāya]| by directing his mind towards it.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, udakamaṇiko pūro udakassa samatittiko kākapeyyo ādhāre ṭhapito. Tamenaṁ balavā puriso yato yato āviñcheyya, āgaccheyya udakan”ti?

Bhikkhus, suppose a water jar is placed on a stand, filled right up to the brim such that crows could drink from it. If a strong man were to tilt it in any direction, would the water flow out?”

“Evaṁ, bhante”.

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā so, yassa yassa abhiññāsacchikaraṇīyassa dhammassa cittaṁ abhininnāmeti abhiññāsacchikiriyāya, tatra tatreva sakkhibhabbataṁ pāpuṇāti sati satiāyatane.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, same bhūmibhāge caturassā pokkharaṇī assa āḷibandhā pūrā udakassa samatittikā kākapeyyā. Tamenaṁ balavā puriso yato yato āḷiṁ muñceyya āgaccheyya udakan”ti?

Bhikkhus, imagine a four-sided pond on level ground, enclosed by |embankments::a wall or bank of earth or stone built to prevent a water body flooding an area [ālibaddhā]|, filled with water up to the brim. If a strong man were to breach the embankment at any point, would the water flow out?”

“Evaṁ, bhante”.

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, so yassa yassa abhiññāsacchikaraṇīyassa dhammassa cittaṁ abhininnāmeti abhiññāsacchikiriyāya, tatra tatreva sakkhibhabbataṁ pāpuṇāti sati satiāyatane.

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, subhūmiyaṁ catumahāpathe ājaññaratho yutto assa ṭhito odhastapatodo; tamenaṁ dakkho yoggācariyo assadammasārathi abhiruhitvā vāmena hatthena rasmiyo gahetvā dakkhiṇena hatthena patodaṁ gahetvā yenicchakaṁ yadicchakaṁ sāreyyāpi paccāsāreyyāpi; evameva kho, bhikkhave, yassa kassaci kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā, so yassa yassa abhiññāsacchikaraṇīyassa dhammassa cittaṁ abhininnāmeti abhiññāsacchikiriyāya, tatra tatreva sakkhibhabbataṁ pāpuṇāti sati satiāyatane.

Bhikkhus, imagine a chariot yoked to thoroughbred horses standing ready at a level crossroads, with a whip ready at hand. A skilled horse-taming charioteer, a master trainer, mounts it, takes the reins with his left hand and the whip with his right, and drives it forward or back wherever he wishes. So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Ten Benefits of Mindfulness of the Body

Kāyagatāya, bhikkhave, satiyā āsevitāya bhāvitāya bahulīkatāya yānīkatāya vatthukatāya anuṭṭhitāya paricitāya susamāraddhāya dasānisaṁsā pāṭikaṅkhā.

Bhikkhus, when mindfulness of the body is practiced, |cultivated::developed [bhāvita]|, frequently practiced, made a vehicle, made a basis, firmly established, consolidated, and |resolutely undertaken::fully engaged with, energetically taken up [susamāraddha]|, ten benefits can be expected.

Aratiratisaho hoti, na ca taṁ arati sahati, uppannaṁ aratiṁ abhibhuyya viharati.

1.) One becomes a conqueror of |discontent::dislike, dissatisfaction, aversion, boredom [arati]| and |delight::relish, liking, pleasure [rati]|, and discontent does not |overcome::overpower, subdue [sahati]| one. One dwells overcoming any discontent that has arisen.

Bhayabheravasaho hoti, na ca taṁ bhayabheravaṁ sahati, uppannaṁ bhayabheravaṁ abhibhuyya viharati.

2.) One becomes a conqueror of |fear::panic, scare, dread, terror [bhaya]| and terror, and fear and terror does not overcome one. One dwells overcoming any fear and terror that has arisen.

Khamo hoti sītassa uṇhassa jighacchāya pipāsāya ḍaṁsamakasavātātapasarīsapasamphassānaṁ duruttānaṁ durāgatānaṁ vacanapathānaṁ, uppannānaṁ sārīrikānaṁ vedanānaṁ dukkhānaṁ tibbānaṁ kharānaṁ kaṭukānaṁ asātānaṁ amanāpānaṁ pāṇaharānaṁ adhivāsakajātiko hoti.

3.) One is |able to [patiently] endure::patient with, forbearing with [khama]| cold and heat, hunger and thirst, the contact of flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun, and creeping creatures; ill-spoken and unwelcome words; and arisen bodily feelings that are painful, intense, harsh, sharp, disagreeable, unpleasant, and even life-threatening.

Catunnaṁ jhānānaṁ ābhicetasikānaṁ diṭṭhadhammasukhavihārānaṁ nikāmalābhī hoti akicchalābhī akasiralābhī.

4.) One obtains at will, without difficulty or trouble, the four jhānas—higher states of mind that provide a pleasant abiding here and now.

So anekavihitaṁ iddhividhaṁ paccānubhoti. Ekopi hutvā bahudhā hoti, bahudhāpi hutvā eko hoti, āvibhāvaṁ …pe… yāva brahmalokāpi kāyena vasaṁ vatteti.

5.) One experiences various types of |psychic powers::supernormal abilities, psychic potency, spiritual power [iddhi]|—becoming one, he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one; he appears and disappears; he passes through walls, enclosures, and mountains unhindered, as if through space; he dives into and emerges from the earth, as if it were water; he walks on water without sinking as though on solid ground; he flies cross-legged through the sky, like a bird. With his hand, he touches and strokes the moon and the sun, so mighty and powerful. And with his body, he exercises control even as far as the |Brahma::God, the first deity to be born at the beginning of a new cosmic cycle and whose lifespan lasts for the entire cycle [brahmā]| world.

Dibbāya sotadhātuyā visuddhāya atikkantamānusikāya ubho sadde suṇāti dibbe ca mānuse ca, ye dūre santike ca …pe….

6.) With the |divine ear element::clairaudience, the divine auditory faculty [dibba + sotadhātu]|, purified and surpassing the human, one hears both kinds of sounds — divine and human — whether they are far or near.

Parasattānaṁ parapuggalānaṁ cetasā ceto paricca pajānāti. Sarāgaṁ vā cittaṁ ‘sarāgaṁ cittan’ti pajānāti, vītarāgaṁ vā cittaṁ …pe… sadosaṁ vā cittaṁ … vītadosaṁ vā cittaṁ … samohaṁ vā cittaṁ … vītamohaṁ vā cittaṁ … saṅkhittaṁ vā cittaṁ … vikkhittaṁ vā cittaṁ … mahaggataṁ vā cittaṁ … amahaggataṁ vā cittaṁ … sauttaraṁ vā cittaṁ … anuttaraṁ vā cittaṁ … samāhitaṁ vā cittaṁ … asamāhitaṁ vā cittaṁ … vimuttaṁ vā cittaṁ … avimuttaṁ vā cittaṁ ‘avimuttaṁ cittan’ti pajānāti.

7.) One discerns the minds of other beings and other persons by encompassing them with their own mind. One knows a mind with lust as ‘a mind with lust’ and a mind without lust as ‘a mind without lust.’ One knows a mind with hatred as ‘a mind with hatred’ and a mind without hatred as ‘a mind without hatred.’ One knows a mind with delusion as ‘a mind with delusion’ and a mind without delusion as ‘a mind without delusion.’ One knows a contracted mind as ‘a contracted mind’ and a scattered mind as ‘a scattered mind.’ One knows an exalted mind as ‘an exalted mind’ and an unexalted mind as ‘an unexalted mind.’ One knows a surpassable mind as ‘a surpassable mind’ and an unsurpassable mind as ‘an unsurpassable mind.’ One knows a collected mind as ‘a collected mind’ and a distracted mind as ‘a distracted mind.’ One knows a liberated mind as ‘a liberated mind’ and an unliberated mind as ‘an unliberated mind.’”

So anekavihitaṁ pubbenivāsaṁ anussarati, seyyathidaṁ—ekampi jātiṁ dvepi jātiyo …pe… iti sākāraṁ sauddesaṁ anekavihitaṁ pubbenivāsaṁ anussarati.

8.) One recollects their manifold past lives, that is, one birth, two births, three births, four, five, ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, a hundred births, a thousand births, a hundred thousand births; many |aeon::lifespan of a world system, a vast cosmic time span [kappa]|s of cosmic contraction, many aeons of cosmic expansion, many aeons of cosmic contraction and expansion: ‘There I was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance, such was my food, such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my life-span; passing away from there, I was reborn elsewhere; there too I was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance, such was my food, such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my life-span; passing away from there, I was reborn here.’ Thus one recollects their manifold past lives with their aspects and in detail.

Dibbena cakkhunā visuddhena atikkantamānusakena satte passati cavamāne upapajjamāne hīne paṇīte suvaṇṇe dubbaṇṇe, sugate duggate yathākammūpage satte pajānāti.

9.) With the |divine eye::the faculty of clairvoyance, the ability to see beyond the ordinary human range [dibbacakkhu]|, purified and surpassing the human, one sees beings passing away and being reborn—inferior and superior, beautiful and ugly, in fortunate and unfortunate destinations—and he understands how beings fare |according to their kamma::in line with their actions [yathākammūpaga]|.

Āsavānaṁ khayā anāsavaṁ cetovimuttiṁ paññāvimuttiṁ diṭṭheva dhamme sayaṁ abhiññā sacchikatvā upasampajja viharati.

10.) Through the |wearing away::exhaustion, depletion, gradual destruction [khaya]| of the |mental defilements::mental outflows, discharges, taints [āsava]|, one realizes for oneself through direct knowledge, the taintless |liberation of mind::mental liberation, emancipation of heart, a meditation attainment [cetovimutti]| and |liberation by wisdom::emancipation by insight [paññāvimutti]|. In this very life, having attained it, one abides in it.

Kāyagatāya, bhikkhave, satiyā āsevitāya bhāvitāya bahulīkatāya yānīkatāya vatthukatāya anuṭṭhitāya paricitāya susamāraddhāya ime dasānisaṁsā pāṭikaṅkhā”ti.

Bhikkhus, when mindfulness of the body is practiced, cultivated, frequently practiced, made a vehicle, made a basis, firmly established, consolidated, and resolutely undertaken, these ten benefits can be expected.

Idamavoca bhagavā. Attamanā te bhikkhū bhagavato bhāsitaṁ abhinandunti.

The Blessed One said this. The bhikkhus were delighted and pleased with the Blessed One’s words.

Thus have I heard—At one time, the Blessed One was dwelling at Sāvatthi, in Jeta’s grove, Anāthapiṇḍika’s park.

Then, after their meal, when many bhikkhus had returned from their alms round and were seated together in the assembly hall, this |this conversation::this discussion, lit. this in-between talk [ayamantarākathā]| arose among them:

“It is wonderful, friends, it is marvelous, how the Blessed One who knows and sees, the |Arahant::a worthy one, a fully awakened being, epithet of the Buddha [arahant]|, the perfectly Awakened One, has said that mindfulness of the body, when cultivated and frequently practiced, is of great fruit and great benefit.”

And this discussion among the bhikkhus was left unfinished. For the Blessed One, having emerged from |seclusion::solitude, privacy [paṭisallāna]| in the late afternoon, approached the assembly hall, and sat down on the prepared seat. Once he was seated, the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus: “Bhikkhus, for what topic of conversation are you now seated together here? And what was the discussion among you that was left unfinished?”

“Here, venerable sir, after we had returned from our alms round following the meal, we were seated together in the assembly hall when this conversation arose among us: ‘It is wonderful, friends, it is marvelous, how the Blessed One who knows and sees, the Arahant, the perfectly Awakened One, has said that mindfulness of the body, when cultivated and frequently practiced, is of great fruit and great benefit.’ And this was the discussion, venerable sir, that was left unfinished when the Blessed One arrived.”

“And how, bhikkhus, is mindfulness of the body cultivated and frequently practiced so that it is of great fruit and great benefit?

Body Contemplation with Breathing

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, having gone to the forest, to the foot of a tree, or to an empty dwelling, sits down, folding his legs crosswise, setting his body upright, establishing mindfulness as first priority. Ever mindful, he breathes in; ever mindful, he breathes out. Breathing in long, he |discerns::distinguishes, understands, knows clearly [pajānāti]|, ‘I am breathing in long;’ breathing out long, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out long.’ Breathing in short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing in short;’ breathing out short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out short.’ He trains thus, ‘While breathing in, I shall |experience the whole body::be conscious of the whole body, be sensitive to the whole process [sabbakāyapaṭisaṃvedī]|;’ he trains thus, ‘While breathing out, I shall experience the whole body.’ He trains thus, ‘While breathing in, I shall |settle::calm, still [passambhayanta]| the |bodily constructs::bodily processes associated with breathing, specifically the in-and-out breath. It encompasses the physical movements and sensations that arise from the act of breathing. [kāyasaṅkhāra]|;’ he trains thus, ‘While breathing out, I shall settle the bodily constructs.’ As he dwells thus—|diligent::doing one’s work or duty well, with alertness, carefulness and care [appamatta]|, |resolute::determined, intent [pahitatta]|, and |with continuous effort::ardent, zealous, with energy, with application [ātāpī]|—his worldly |memories and thoughts::memories and plans [sarasaṅkappā]| are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and |collected::composed, stable [samādhiyati]|. In this way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Body Contemplation in Postures

Furthermore, bhikkhus, when walking, a bhikkhu discerns, ‘I am walking;’ when standing, he discerns, ‘I am standing;’ when sitting, he discerns, ‘I am seated;’ when lying down, he discerns, ‘I am lying down.’ In whatever way his body is |oriented::disposed; lit. placed down forward [paṇihita]|, he discerns it accordingly. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Body Contemplation with Clear Awareness

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu acts with |clear awareness::attentiveness, clear and full comprehension [sampajañña]| when going forward and returning; he acts with clear awareness when looking ahead and looking around; he acts with clear awareness when bending back and stretching out; he acts with clear awareness when wearing robes and carrying outer robe and bowl; he acts with clear awareness when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting; he acts with clear awareness when defecating and urinating; he acts with clear awareness when walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, waking up, speaking, and keeping silent. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Contemplating the Disagreeable in the Body

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu |reviews::considers, reflects, regards [paccavekkhati]| this very body from the soles of the feet upwards and from the top of the hair downwards, bounded by skin and full of various impurities thus: ‘In this body, there are hairs of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin; flesh, |sinews::tendons and ligaments connecting muscle to bone [nhāru]|, bones, |bone marrow::the soft tissue inside the bones [aṭṭhimiñjaṁ]|, kidneys; heart, liver, |inner membrane::the pleura or fascia wrapping the organs [kilomaka]|, |spleen::the blood-filtering organ under the left ribs [pihaka]|, lungs; intestines, |mesentery::the tissue binding the intestines; lit. intestine string [antaguṇa]|, |stomach contents::undigested food; lit. related to the belly [udariya]|, |feces::excrement, digested waste [karīsaṁ]|, [brain]; |bile::digestive fluid, usually visualized in the gall bladder [pittaṁ]|, |phlegm::mucus of the respiratory tract [semha]|, |pus::fluid resulting from infection or decay [pubba]|, blood, |sweat::perspiration exuded from pore spaces [seda]|, |fat::thick, adipose tissue [meda]|, tears, |grease::liquid fat or skin oils (distinct from solid fat) [vasā]|, saliva, |nasal mucus::snot, fluid from the nose [siṅghāṇikā]|, |synovial fluid::lubricating fluid inside the joints [lasikā]|, and |urine::liquid waste stored in the bladder [mutta]|.’

Just as if, bhikkhus, there were a bag with an opening at both ends full of many sorts of grains, such as rice, barley, beans, peas, millet, and white rice, and a man with good eyesight having opened it were to reflect, ‘These are rice, these are barley, these are beans, these are peas, these are millet, these are white rice.’ In just the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body from the soles of the feet upwards and from the top of the hair downwards, bounded by skin and full of various impurities thus: ‘In this body, there are hairs of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin; flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys; heart, liver, inner membrane, spleen, lungs; intestines, mesentery, stomach contents, feces, [brain]; bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid, and urine.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Contemplating the Elements in the Body

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body, in whatever way it is positioned, in whatever way it is oriented, considering it in terms of the elements thus: ‘In this body, there is the |earth element::whatever internal or external that is solid, hard, resistant, appears stable and supporting, which can be considered as belonging to oneself, and can be clung to [pathavīdhātu]|, the |water element::whatever internal or external, that is liquid, cohesive, flowing, binding, moist, which can be considered as belonging to oneself, and can be clung to [āpodhātu]|, the |fire element::whatever internal or external that is hot, fiery, transformative, warming, cooling, which can be considered as belonging to oneself and can be clung to [tejodhātu]|, and the |wind element::whatever internal or external that is airy, gaseous, moving, vibrating, wind-like, which can be considered as belonging to oneself and can be clung to [vāyodhātu]|.’

Just as if, bhikkhus, a skilled butcher or their apprentice, having slaughtered a cow, were sitting at a crossroads, having divided it up piece by piece; in just the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this very body, however it is positioned, in whatever way it is oriented, considering it in terms of the elements thus: ‘In this body, there is the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the wind element.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

The Nine Charnel Ground Contemplations

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a |charnel ground::an above-ground site for the putrefaction of bodies, generally human, where formerly living tissue is left to decompose uncovered [sivathikā]| one day dead, two days dead, or three days dead, bloated, discolored, and decomposing, a bhikkhu |compares::likens; lit. brings near together [upasaṁharati]| this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, being eaten by crows, or hawks, or vultures, or herons, or dogs, or tigers, or leopards, or jackals, or by various kinds of creatures, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, a skeleton with flesh and blood and held together by sinews; or a skeleton without flesh but smeared with blood and held together by sinews; or a skeleton devoid of flesh and blood and held together by sinews; or bones disconnected and scattered in all directions—here a hand bone, there a foot bone, there an ankle bone, here a shin bone, there a thigh bone, here a pelvis bone, there a rib, here a spine, there a shoulder blade, here a neck bone, there a jawbone, here a tooth, and there a skull, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, just as if he saw a corpse thrown in a charnel ground, bones bleached white, the color of conch shells; or bones heaped up, having lain for more than a year; or bones that are rotten and reduced to dust, a bhikkhu compares this very body to it thus: ‘This body too is of the same nature; it will become like that; it is not exempt from that fate.’ As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Four Jhānas

Furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, quite secluded from sensual pleasures and |unwholesome::unhealthy, unskillful, unbeneficial, or karmically unprofitable [akusala]| mental states, enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is |accompanied by reflection::with thinking [savitakka]| and |examination::with investigation, evaluation [savicāra]|, |born of seclusion::secluded from the defilements [vivekaja]|, and imbued with |uplifting joy and pleasure::delight and ease; sometimes experienced as ecstasy, intense exhilaration or rapture [pītisukha]|. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of seclusion, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by the uplifting joy born of seclusion. Just as a skilled bath attendant or his apprentice might knead bathing powder in a bronze bowl, sprinkling water again and again until the lump becomes permeated with moisture, saturated inside and out, yet does not drip. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of seclusion, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by the uplifting joy born of seclusion. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the |settling::calming, conciliation, subsiding [vūpasama]| of reflection and examination, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the second jhāna, characterized by internal |tranquility::calming, settling, confidence [sampasādana]| and |unification::singleness, integration [ekodibhāva]| of mind, free from reflection and examination, |born of collectedness::born from a stable mind [samādhija]|, and imbued with |uplifting joy and pleasure::delight and ease; sometimes experienced as ecstasy, intense exhilaration or rapture [pītisukha]|. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with uplifting joy born of collectedness, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by uplifting joy born of collectedness. Just as a deep lake fed by an underground spring—with no inflow from the east direction, west direction, north direction, or the south direction, and no rainclouds showering water—would have cool streams welling up from within to thoroughly suffuse, pervade, fill, and permeate the entire lake, leaving no part uncovered by cool water. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with the uplifting joy born of collectedness, so that there is no part of his body not suffused by uplifting joy born of collectedness. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the |fading of desire for::dispassion toward, detachment from [virāga]| uplifting joy, the bhikkhu dwells |equanimous::mental poised, mentally balanced, non-reactive, disregarding [upekkhaka]|, |mindful and clearly aware::attentive and completely comprehending [sata + sampajāna]|, experiencing |pleasure::comfort, contentedness, happiness, ease [sukha]| with the body. He enters and dwells in the third jhāna, which the Noble Ones describe as, ‘one who dwells equanimous, mindful, and at ease.’ He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with pleasure devoid of delight, so that there is no part of his entire body that is not suffused with pleasure devoid of delight. Just as, bhikkhus, in a pond of blue, red, or white lotuses, some lotuses born in the water grow entirely submerged, and remain nourished from within by cool water that thoroughly suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates them from their tips to their roots, leaving no part untouched by cool water. In the same way, bhikkhus, the bhikkhu suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with pleasure devoid of delight, so that there is no part of his body that is not suffused with pleasure devoid of delight. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Furthermore, bhikkhus, with the abandoning of [bodily] pleasure and |pain::discomfort, unpleasantness. In this context, this is referring to bodily pain or sharp sensations. [dukkha]|, and with the prior settling down of |mental pleasure and displeasure::the duality of positive and negative states of mind; mental happiness and mental pain [somanassadomanassa]|, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the fourth jhāna, which is characterized by purification of |mindfulness::recollection of the body, feelings, mind, and mental qualities, observing them clearly with sustained attention, free from craving and distress [sati]| through |equanimity::mental poise, mental balance, equipoise, non-reactivity, composure [upekkhā]|, experiencing a feeling which is neither-painful-nor-pleasant. He suffuses, pervades, fills, and permeates his entire body with a purified and clear mind, so that there is no part of his body that is not suffused by this purified and clear mind. Just as, bhikkhus, a person covered from head to toe in a spotless white cloth with no part of his body uncovered. In the same way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu sits pervading this very body with a pure mind, so purified and clarified, that there is no part of his whole body not pervaded by the pure mind. As he dwells thus—diligent, resolute, and with continuous effort—his worldly memories and thoughts are abandoned. With the abandonment of those thoughts, his mind becomes internally steady, calmed, unified, and collected. In this way too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu cultivates mindfulness of the body.

Similes

For whomever, bhikkhus, mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, all beneficial |mental qualities::characteristics, traits, and tendencies of the mind, shaped by repeated actions and sustained attention, guided by particular ways of understanding; they may be wholesome or unwholesome, bright or dark [dhammā]| pertaining to wisdom are included within him. Just as, bhikkhus, for whomever the great ocean is encompassed by his mind, all the small rivers that flow to the ocean are included within that; so too, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, all beneficial mental qualities pertaining to wisdom are included within him.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, |Māra::the ruler of the sensual realm, often depicted as a tempter who tries to obstruct beings from the path to liberation [māra]| finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him. Suppose, bhikkhus, a man were to throw a heavy lump of rock upon a mound of wet clay.

What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that heavy lump of rock find an opening in that mound of wet clay?”

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a dry sapless piece of wood, and a man were to come with an upper fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by rubbing the dry sapless piece of wood with an upper fire-stick?”

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a hollow empty water jar placed on a stand, and a man were to come carrying a load of water.

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could that man pour the water into it?”

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is not cultivated and not frequently practiced, Māra finds an opening in him; Māra gains a foothold in him.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Suppose, bhikkhus, a man were to throw a light ball of string onto a door-panel made entirely of heartwood.

What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that light ball of string find an opening in that door-panel made entirely of heartwood?”

“No, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a wet sappy piece of wood, and a man were to come with an upper fire-stick, thinking: ‘I shall light a fire, I shall produce heat.’

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could the man light a fire and produce heat by rubbing the wet sappy piece of wood with an upper fire-stick?”

“No, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Suppose, bhikkhus, there were a water jar placed on a stand, filled right up to the brim such that crows could drink from it, and a man were to come carrying a load of water.

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could that man pour the water into it?”

“No, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, Māra does not find an opening in him; Māra does not gain a foothold in him.

Bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by |direct knowledge::experiential understanding [abhiññāya]| by directing his mind towards it.

Bhikkhus, suppose a water jar is placed on a stand, filled right up to the brim such that crows could drink from it. If a strong man were to tilt it in any direction, would the water flow out?”

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Bhikkhus, imagine a four-sided pond on level ground, enclosed by |embankments::a wall or bank of earth or stone built to prevent a water body flooding an area [ālibaddhā]|, filled with water up to the brim. If a strong man were to breach the embankment at any point, would the water flow out?”

“Yes, venerable sir.”

“So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Bhikkhus, imagine a chariot yoked to thoroughbred horses standing ready at a level crossroads, with a whip ready at hand. A skilled horse-taming charioteer, a master trainer, mounts it, takes the reins with his left hand and the whip with his right, and drives it forward or back wherever he wishes. So too, bhikkhus, for whomever mindfulness of the body is cultivated and frequently practiced, then, there being a suitable basis, the bhikkhu is capable of realizing any phenomenon realizable by direct knowledge by directing his mind towards it.

Ten Benefits of Mindfulness of the Body

Bhikkhus, when mindfulness of the body is practiced, |cultivated::developed [bhāvita]|, frequently practiced, made a vehicle, made a basis, firmly established, consolidated, and |resolutely undertaken::fully engaged with, energetically taken up [susamāraddha]|, ten benefits can be expected.

1.) One becomes a conqueror of |discontent::dislike, dissatisfaction, aversion, boredom [arati]| and |delight::relish, liking, pleasure [rati]|, and discontent does not |overcome::overpower, subdue [sahati]| one. One dwells overcoming any discontent that has arisen.

2.) One becomes a conqueror of |fear::panic, scare, dread, terror [bhaya]| and terror, and fear and terror does not overcome one. One dwells overcoming any fear and terror that has arisen.

3.) One is |able to [patiently] endure::patient with, forbearing with [khama]| cold and heat, hunger and thirst, the contact of flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun, and creeping creatures; ill-spoken and unwelcome words; and arisen bodily feelings that are painful, intense, harsh, sharp, disagreeable, unpleasant, and even life-threatening.

4.) One obtains at will, without difficulty or trouble, the four jhānas—higher states of mind that provide a pleasant abiding here and now.

5.) One experiences various types of |psychic powers::supernormal abilities, psychic potency, spiritual power [iddhi]|—becoming one, he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one; he appears and disappears; he passes through walls, enclosures, and mountains unhindered, as if through space; he dives into and emerges from the earth, as if it were water; he walks on water without sinking as though on solid ground; he flies cross-legged through the sky, like a bird. With his hand, he touches and strokes the moon and the sun, so mighty and powerful. And with his body, he exercises control even as far as the |Brahma::God, the first deity to be born at the beginning of a new cosmic cycle and whose lifespan lasts for the entire cycle [brahmā]| world.

6.) With the |divine ear element::clairaudience, the divine auditory faculty [dibba + sotadhātu]|, purified and surpassing the human, one hears both kinds of sounds — divine and human — whether they are far or near.

7.) One discerns the minds of other beings and other persons by encompassing them with their own mind. One knows a mind with lust as ‘a mind with lust’ and a mind without lust as ‘a mind without lust.’ One knows a mind with hatred as ‘a mind with hatred’ and a mind without hatred as ‘a mind without hatred.’ One knows a mind with delusion as ‘a mind with delusion’ and a mind without delusion as ‘a mind without delusion.’ One knows a contracted mind as ‘a contracted mind’ and a scattered mind as ‘a scattered mind.’ One knows an exalted mind as ‘an exalted mind’ and an unexalted mind as ‘an unexalted mind.’ One knows a surpassable mind as ‘a surpassable mind’ and an unsurpassable mind as ‘an unsurpassable mind.’ One knows a collected mind as ‘a collected mind’ and a distracted mind as ‘a distracted mind.’ One knows a liberated mind as ‘a liberated mind’ and an unliberated mind as ‘an unliberated mind.’”

8.) One recollects their manifold past lives, that is, one birth, two births, three births, four, five, ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, a hundred births, a thousand births, a hundred thousand births; many |aeon::lifespan of a world system, a vast cosmic time span [kappa]|s of cosmic contraction, many aeons of cosmic expansion, many aeons of cosmic contraction and expansion: ‘There I was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance, such was my food, such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my life-span; passing away from there, I was reborn elsewhere; there too I was so named, of such a clan, with such an appearance, such was my food, such my experience of pleasure and pain, such my life-span; passing away from there, I was reborn here.’ Thus one recollects their manifold past lives with their aspects and in detail.

9.) With the |divine eye::the faculty of clairvoyance, the ability to see beyond the ordinary human range [dibbacakkhu]|, purified and surpassing the human, one sees beings passing away and being reborn—inferior and superior, beautiful and ugly, in fortunate and unfortunate destinations—and he understands how beings fare |according to their kamma::in line with their actions [yathākammūpaga]|.

10.) Through the |wearing away::exhaustion, depletion, gradual destruction [khaya]| of the |mental defilements::mental outflows, discharges, taints [āsava]|, one realizes for oneself through direct knowledge, the taintless |liberation of mind::mental liberation, emancipation of heart, a meditation attainment [cetovimutti]| and |liberation by wisdom::emancipation by insight [paññāvimutti]|. In this very life, having attained it, one abides in it.

Bhikkhus, when mindfulness of the body is practiced, cultivated, frequently practiced, made a vehicle, made a basis, firmly established, consolidated, and resolutely undertaken, these ten benefits can be expected.

The Blessed One said this. The bhikkhus were delighted and pleased with the Blessed One’s words.

Evaṁ me sutaṁ—ekaṁ samayaṁ bhagavā sāvatthiyaṁ viharati jetavane anāthapiṇḍikassa ārāme.

Atha kho sambahulānaṁ bhikkhūnaṁ pacchābhattaṁ piṇḍapātapaṭikkantānaṁ upaṭṭhānasālāyaṁ sannisinnānaṁ sannipatitānaṁ ayamantarākathā udapādi:

“acchariyaṁ, āvuso, abbhutaṁ, āvuso. Yāvañcidaṁ tena bhagavatā jānatā passatā arahatā sammāsambuddhena kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā mahapphalā vuttā mahānisaṁsā”ti.

Ayañca hidaṁ tesaṁ bhikkhūnaṁ antarākathā vippakatā hoti, atha kho bhagavā sāyanhasamayaṁ paṭisallānā vuṭṭhito yena upaṭṭhānasālā tenupasaṅkami; upasaṅkamitvā paññatte āsane nisīdi. Nisajja kho bhagavā bhikkhū āmantesi: “kāya nuttha, bhikkhave, etarahi kathāya sannisinnā, kā ca pana vo antarākathā vippakatā”ti?

“Idha, bhante, amhākaṁ pacchābhattaṁ piṇḍapātapaṭikkantānaṁ upaṭṭhānasālāyaṁ sannisinnānaṁ sannipatitānaṁ ayamantarākathā udapādi: ‘acchariyaṁ, āvuso, abbhutaṁ, āvuso. Yāvañcidaṁ tena bhagavatā jānatā passatā arahatā sammāsambuddhena kāyagatāsati bhāvitā bahulīkatā mahapphalā vuttā mahānisaṁsā’ti. Ayaṁ kho no, bhante, antarākathā vippakatā, atha bhagavā anuppatto”ti.

“Kathaṁ bhāvitā ca, bhikkhave, kāyagatāsati kathaṁ bahulīkatā mahapphalā hoti mahānisaṁsā?

Idha, bhikkhave, bhikkhu araññagato vā rukkhamūlagato vā suññāgāragato vā nisīdati pallaṅkaṁ ābhujitvā ujuṁ kāyaṁ paṇidhāya parimukhaṁ satiṁ upaṭṭhapetvā. So satova assasati satova passasati; dīghaṁ vā assasanto ‘dīghaṁ assasāmī’ti pajānāti, dīghaṁ vā passasanto ‘dīghaṁ passasāmī’ti pajānāti; rassaṁ vā assasanto ‘rassaṁ assasāmī’ti pajānāti, rassaṁ vā passasanto ‘rassaṁ passasāmī’ti pajānāti; ‘sabbakāyapaṭisaṁvedī assasissāmī’ti sikkhati, ‘sabbakāyapaṭisaṁvedī passasissāmī’ti sikkhati; ‘passambhayaṁ kāyasaṅkhāraṁ assasissāmī’ti sikkhati, ‘passambhayaṁ kāyasaṅkhāraṁ passasissāmī’ti sikkhati. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.

Puna caparaṁ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu gacchanto vā ‘gacchāmī’ti pajānāti, ṭhito vā ‘ṭhitomhī’ti pajānāti, nisinno vā ‘nisinnomhī’ti pajānāti, sayāno vā ‘sayānomhī’ti pajānāti. Yathā yathā vā panassa kāyo paṇihito hoti tathā tathā naṁ pajānāti. Tassa evaṁ appamattassa ātāpino pahitattassa viharato ye gehasitā sarasaṅkappā te pahīyanti. Tesaṁ pahānā ajjhattameva cittaṁ santiṭṭhati sannisīdati ekodi hoti samādhiyati. Evampi, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāyagatāsatiṁ bhāveti.